At first glance, the Cycling merit badge seems like one of those merit badges that just about any Scouter could teach (assuming he or she is registered as a merit badge counselor). After all, you really never forget how to ride a bike. But a counselor who’s an avid cyclist can make the badge more than an exercise in logging miles and checking off requirements — he or she can introduce Scouts to a sport they can pursue for a lifetime.

Brian Burnham is a good example. An assistant Scoutmaster with Troop 845 in Chapel Hill, N.C., he has led Scouts on four cross-country bike trips since 2005. One of his Scouts went on to compete in triathlons and won the youth division of the first Half Ironman he entered.

Craig McNeil is another good example. An early proponent of adding a mountain-biking component to the Cycling merit badge, McNeil, who lives in Denver, has introduced hundreds of Scouts to the sport at Timberline District camporees.

Scouting talked with Burnham and McNeil to get their insights on teaching the Cycling merit badge.

What to ride

High-end bikes can cost thousands of dollars, but Burnham said Scouts can complete the merit badge — and much more — without spending much money.

“I’ve ridden across the U.S. four times on a bike that cost me $275,” he says. “I just give her some TLC on the back porch after every tour, and then she’s ready to roll again the next time.”

Basic maintenance is even more important with bikes that go off road.

“Any kind of grit that gets into the bearings will affect the longevity of the bike if you don’t take care of it,” McNeil says.

McNeil, who rides a 10- or 15-year-old bike, says good used bikes are easy to come by at local bike shops and through buy-and-sell websites.

“People who are serious riders tend to feel like they need to be the early adopters in getting the latest and greatest,” he says.

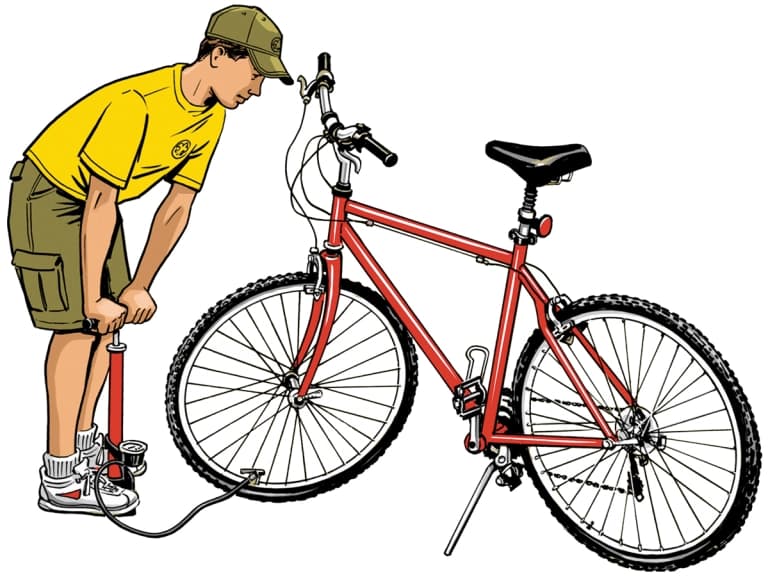

Bike maintenance

Teaching bike maintenance might be the biggest challenge for counselors who are casual cyclists. Burnham has recruited bike-shop mechanics to bring tools and repair stands to a troop meeting.

“They give a 45-minute academic overview of what we’re going to do, then the Scouts dig in,” he says. “Each one fully breaks down his own bike and rebuilds it by changing tubes, setting up brakes and working on the drive train.”

McNeil recommends doing much the same thing. He also emphasizes the importance of being able to change a tire.

“When you’re out, you’re going to get flat tires,” he says. “It’s more likely to happen in the woods than on the road.”

Essential skills

For road biking, Scouts must understand traffic laws, how to use their bike’s gears effectively and how to communicate with fellow riders. But Burnham says the most essential skill might be what he calls “car management.”

For example, a rider can discourage a car from passing him in a blind curve by drifting away from the shoulder. Then, when it’s safe to pass and the car moves across the center line, he can drift back to the shoulder to allow extra passing room.

“It’s a little weird for young cyclists to do that, but it’s kind of cool to watch,” he says.

Burnham recommends having a classroom session on road safety, followed by a one-hour ride, followed by an after-ride safety discussion.

“I repeat this process for a number of our 10-mile rides and also for our 50-mile ride,” he says.

In the world of mountain biking, essential skills are balance, dexterity and focus. McNeil recommends spending time in a parking lot working on “skills and drills.” For example, you could create a slalom course out of traffic cones or build a small obstacle with 2-by-8 boards that riders must bunny-hop over. He also likes to have riders pick up water bottles from the ground or limbo under a rope hanging loosely across their path. He rediscovered the value of skills and drills after teaching Scouts at his first camporee.

“When I got back on my mountain bike, I was a much better rider,” he says.

Skills and drills can continue once you get on the trail. He recommends finding spots to practice water-bottle pickups or to climb a hill in your lowest gear without stopping.

Photo courtesy of Bartle Scout Reservation

Where to ride

Road cyclists can ride just about anywhere except controlled-access highways, but some routes are better than others.

“With inexperienced Scouts, you’ll want to have big shoulders and low traffic volumes,” Burnham says. He suggests using Google Maps in bike mode or, better yet, asking an experienced cyclist to design some routes based on your Scouts’ skill level.

For mountain-biking trails, McNeil recommends starting with the International Mountain Biking Association website or simply doing a web search on trails in your area.

“I don’t care where you live — Kentucky, Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma — there are plenty of places you can go and get elevation gains, where you can go up a hill and you can go down a hill,” he says.

As with road biking, there are also places to avoid off road.

“You can find some really mild and easy stuff that challenges you with elevation, and you can find other stuff that’s downright gnarly, where you can hurt yourself,” McNeil says. “We try to avoid that at all costs.”

Of course, Scouts can graduate to gnarly trails as they develop better skills just as they can progress from 50-mile rides to cross-country trips. And the fun doesn’t have to end once they earn the merit badge. Several of Burnham’s cross-country riders like to schedule impromptu rides via Facebook.

“It has become a social thing for them,” he says. “Instead of just sitting around, they go out and ride.”